Not Set

The submersible Maria built by John Day for a bet was sunk in Plymouth Sound in 1774, and never returned to the surface.

Type

'Submarine'

Location

Between Drake's Island and Eastern Kings, in Plymouth Sound

History

“...but 'tis generally believed that she bursted as soon as she reached the bottom.”

John Day was a labourer for a shipwright at Yarmouth but he was an ingenious man and he was also fond of money. Day thought that he could make a fortune from building a submarine and making bets that he could stay inside it, underwater, for a whole day. As an experiment, Day took a Norwich market boat and added a small watertight compartment, sank the boat in the Norfolk broads and allowed the tide to submerge the vessel with him inside, remaining there for a few hours as the tide came in and out. Flushed with the success of the first trial, in November 1773 he looked in the Sporting Kalendar for a sponsor for the next part of the enterprise. Day found Christopher Blake, a notorious gambler, and sent him a letter proposing a way of making thousands of pounds for a share of 10 per cent. Blake wrote back to Day and suggested they meet up to discuss the proposal, generously offering to cover Day's travelling expenses even if he did not like the idea.

When Blake and Day met, Day proposed to sink a ship 100 yards (91.5m) deep into the sea for 24 hours then return to the surface unaided and unharmed. Blake was interested but wanted proof of the idea so Day had a model made of the submarine and demonstrated it to his potential sponsor, who then agreed to provide the required funds to build it. To simplify the proposal, Blake reduced the depth to 100 feet (30.5m) and the immersion time to 12 hours. Blake immediately made a bet that this could be done within 3 months, but there was too much to do and time limit expired so Blake lost a lot of money.

Undeterred, Day carried on with his plan and purchased a 50 ton sloop called the Maria from captain and owner Mr Sparks for £340, the Maria was old but still in good condition. In March 1774 the Maria was passed to shipwright Mr Hunn of Plymouth for fitting out where she was caulked, sheathed and repaired as well as being converted for the submarine trials.

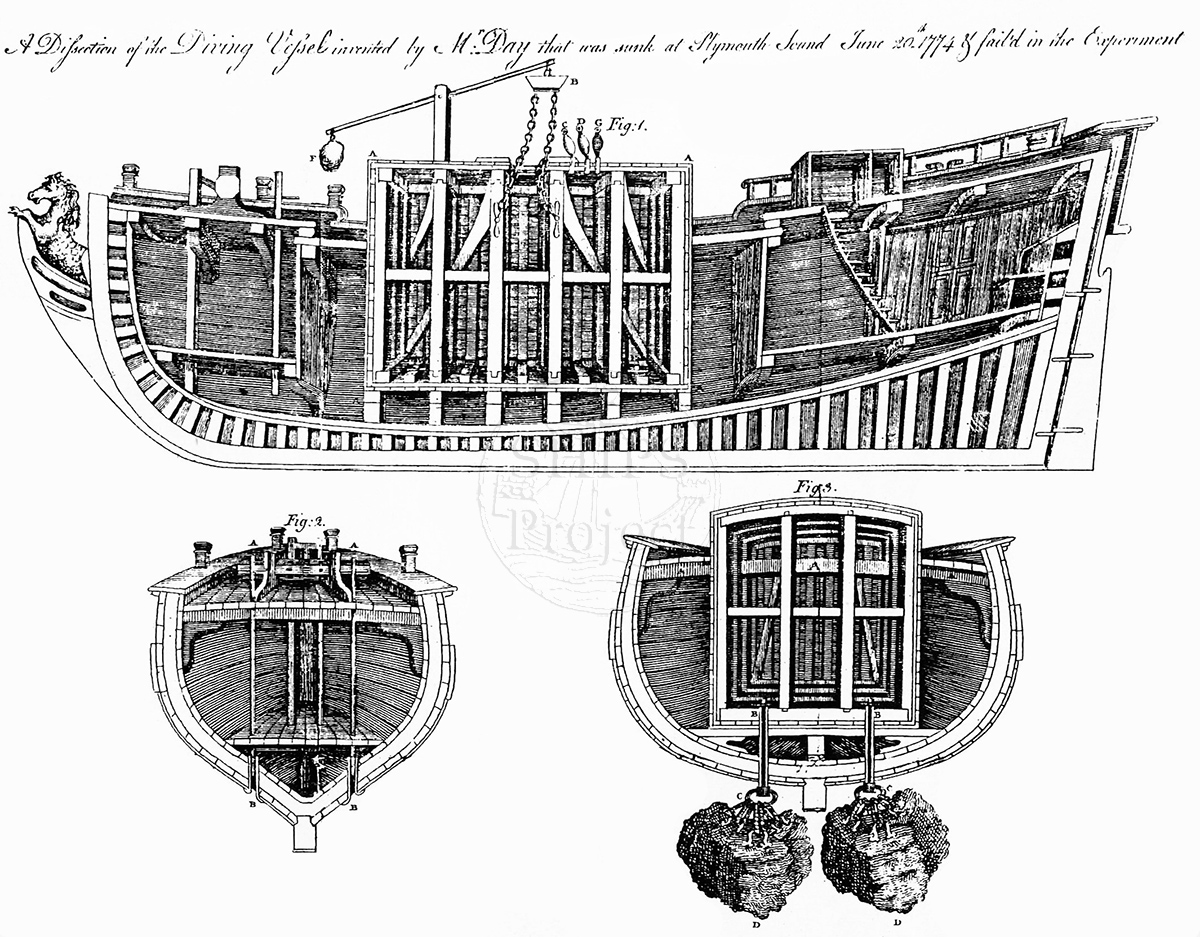

The Maria was small with a 31 foot (9.5m) keel, a beam of 16 feet (4.9m) and hold 9 ft (2.74m) in height. Into the hold of the ship Hunn fitted a box-shaped air chamber 12ft (3.66m) by 9ft (2.74m) by 8ft (2.44m), big enough to contain enough air for 24 hours, calculated as 75 hogsheads or 24.5 cubic metres of air. The air chamber was built around a floor frame of six beams scarfed into two longitudinal beams, vertical uprights attached with reinforcing knees, arched deck beams over the top and diagonal bracing to add strength. The sturdy frame was first covered with two inch planking which was sealed with caulking and pitch, then a second layer of two inch planking was added running in the opposite direction and again caulked and pitched.

A square scuttle or entry hatch was fitted into the roof of the air chamber, tapered and lined with flannel so it would make a watertight seal as the ship submerged. A counterbalance weight was fitted to the outside so the hatch could be opened and closed by Day and four stout chains were fitted to allow the scuttle to be fixed shut from the inside. On the aft upper deck Day also had fitted three floating buoys that could be released from inside the chamber, one of which would be released once he had got to the bottom. A white buoy could be released to indicate that Day was ‘very well’, a red buoy would indicate that he was ‘indifferent’ and if the black ball was released the surface crew would know that day was ‘very ill’.

The air in the chamber would provide 25 tons of buoyancy which was counteracted by external ballast fitted under the ship, along with 10 tons of limestone ballast inside the ship and by flooding the forward and aft spaces in the vessel. The flooding was controlled by four sluice pipes fitted through the hull that could be opened from on deck just before day entered the air chamber before the descent. The external stone ballast was designed to be dropped from the vessel at the end of the dive so Day and the Maria would gently float to the surface. The drop ballast was made up of twenty one-ton rocks attached in groups of five to four iron bolts that passed through lead lined holes through the bottom of the ship and in to the air chamber. The plan was to undo a nut on each bolt which attached the bolt and the ballast to the ship, then quickly hammer in a plug into the hole where the bolt used to be. Quite how Day was to undo each nut when five tons of rock ballast was hanging from each bolt is a mystery, as is his method of plugging the hole against the large pressure of water at 30m depth. Being a confident man, Day did not fit the Maria with any external lifting devices or brackets to be used if the Maria got stuck on the bottom. It is also suggested that Day painted the vessel red before she was put in the water and that she may have had legs fastened to her bottom, standing on feet like a butcher's block.

The prototype submarine was sunk in the Cattewater by putting it aground at low water and letting the tide cover it for a period of six hours, but it was found to be too light to sink. Still confident that his invention would work the Maria was towed out from Sutton Harbour to Firestone Bay on 20th June 1774 for the first demonstration of its capabilities. A barge with Blake on board was anchored in position, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Orpheus was anchored nearby to offer any help that was required with the experiment and on the shore were a few passers by who stopped to watch the activities.

Day went on board the Maria carrying a hammock, a watch, a small candle, a bottle of water and a couple of biscuits. After pulling out the plugs to let water into the vessel, Day found that even with the bow and stern spaces full of water the ship refused to sink. The solution was to add more ballast, so the fore and aft decks were ripped up and stones from the local quarries were dropped in by hired labourers, adding approximately 20 tons to the ballast she already carried. Finally it looked like the Maria would submerge so Day took off his coat and waistcoat claiming that he would have ‘a hot birth of it’, said goodbye, got in the chamber and shut the hatch firmly. The labourers carried on heaving in stones and the Maria sank under water, slightly stern first.

A few minutes after the ship had disappeared, bubbles appeared in the sea above where she sank and was covered with froth for some yards around, seemingly caused by an uprush of air from below. No signal buoy appeared to say how Day was coping with being under water so the onlookers began to get anxious for his safety. Meanwhile, more and more people turned up to watch until the hills overlooking the Sound were covered with spectators. At 2am, the appointed time for surfacing, there was still no sign of the Maria or any buoys released from her. At 7am there was still no sign so Blake asked the captain of the Orpheus and Lord Sandwich to help raise the vessel, thinking that Day would still be alive inside. So for three days 200 dockyard workers manning lighters and lifting cables tried to lift the ship but to no avail. Thinking that day must now be dead the salvage operation was abandoned.

But not everyone thought all was lost including a doctor, N. D. Falck. Falck was a man of many interests who had published an account of an improved steam engine and a ‘Treatise on the Venereal Disease in 3 parts, illustrated with copperplates’. Falck had also published works on accidents and diseases of seamen and thought that the cold at the bottom of the sea may be holding Day in some kind of suspended animation and that if recovered he may be revived. Falck also wanted to find out why the experiment failed and to publish what he found for the pubic good. By contacting the shipwright, Hunn, he managed to get in touch with Blake who gave consent for another salvage attempt. Falck also tried to recruit the services of the Navy again by writing to Lord Sandwich but he wasn’t interested as the Navy considered Day to be definitely and finally dead.

Falck arrived in Plymouth on 28th July 1774 and immediately started preparations to locate the Maria using a sweep search, which was undertaken two days later. The search located fresh timber, pitched and painted red, in 22 fathoms depth at low water, so the site was marked with a buoy. The wreck was found 150 fathoms off the main shore with Drakes Island due south, Firestone Bay north by west, lying on a seabed of soft clay mud. On Monday 1st August two 40 ton barges were brought out and moored near the marker buoy, the barges were lashed together with two massive wooden yards 40ft long and 17 inch in diameter to make a stable catamaran to use as a work platform.

Falck’s first idea was to add buoyancy to the heavy ship by attaching barrels of air to it. Iron harpoons were fabricated which could be driven into the hull using a 50 pound rammer, to which barrels of air could then be hauled down. Falck had difficulty achieving this task as it was done using ropes from the surface in 30m depth in a tideway, so this method was abandoned. The next plan was to haul ropes under the hull, jam them together so they secured the hull in a web of rope, then haul the whole lot to the surface. This was attempted on 3rd August and by the end of the exercise the Maria was hanging from windlasses on the salvage barge. Unfortunately, as often happens, the weather then took charge with a gale and a heavy sea causing a lot of damage to the salvage gear. By 5th the salvage work resumed and on 6th they were ready for the first attempt at a tidal lift, hauling down on the ropes around the Maria at low tide then letting the rising tide pull the wreck from the seabed. Unfortunately the strain on the ropes caused the huge spars holding the barges together to break so work had to stop yet again. The big spars were replaced with two even bigger 60 ft 22in diameter timbers lashed with two smaller spars, the salvage was attempted again but this time only one of the spars broke. On Thursday 11th they succeeded in lifting the hull slightly and moving her a little way before she was again aground, but this spurred on the salvage team who urged Falck to recruit more people. The masters of two colliers and their crews came to assist and they all worked on into the night. On the next attempt a hawser broke and the Maria again slipped to the bottom and on 14th they tried again but this time using sheerlegs fitted to each barge. Again, a damaged hawser slipped and down went the Maria, this time she fell out of her web of ropes so she had to be relocated. Attempts to snare the Maria went on for the next week until they finally had success on Saturday 21st, but hauling her up failed yet again. However, on the last attempt they did manage to disengage the external ballast and so lighten the ship considerably. By the end of August the expensive salvage gear was worn out, as were Dr Falck and the salvage crew, so the job was temporarily abandoned. Falck paid off the crew and headed for home, aiming for another attempt on 21st October, but he never returned.

So the Maria and John Day still lie on the seabed in Plymouth Sound and John Day has the dubious distinction of being the first man to be lost in a submarine accident.

Many people have searched for the remains of this ship over the years, one of the first recorded being in 1979 by BSAC No 1 branch diving club led by Reg Vallintine and assisted by Alan Bax. As yet, no sign of this little vessel has been found.

Digest version, for more information please contact The SHIPS Project.

Location and Access

The location of the wreck is between Drake's Island and Eastern Kings, in Plymouth Sound.

Permission to dive around Drake's Island must be obtained from King’s Harbour Master, Plymouth.

Last updated 04 June 2024

Information

Type:

Submersible

Date Built:

1774

Date of Loss:

20 June 1774

Manner of Loss:

Imploded

Outcome

Salvage attempted, failed

Builder:

John Day

Official Number:

None

Length

9.5m

Beam

4.9m

Depth in Hold

2.74m

Construction

Timber

Propulsion

None

Tonnage

50 tons

Nationality

English

Armament

none

Crew

1

Master

John Day

Owner

Christopher Blake

Reference

None

.

Not Set

Leave a message

Your email address will not be published.

Click the images for a larger version

Image use policy

Our images can be used under a CC attribution non-commercial licence (unless stated otherwise).